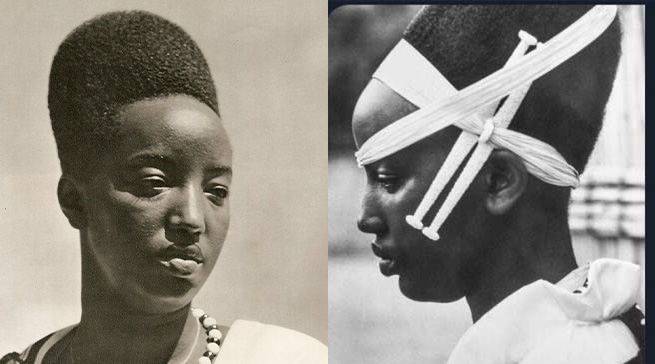

After nearly three decades on the run, Brigadier General Sibo Stany Gakwerere, a key figure in the murder of Rwanda’s last queen, Rosalie Gicanda, has finally fallen into the hands of justice. Captured by M23 rebels in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Gakwerere was handed over to Rwandan authorities today alongside other FDLR fighters. His capture marks the end of a long and brutal legacy of terror.

A notorious figure in the Rwandan Armed Forces during the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, Gakwerere was part of the elite group from ESO (École des Sous-Officiers) and Camp Ngoma, responsible for some of the most heinous crimes in Butare. Alongside Lieutenant Colonel Tharcisse Muvunyi and Adjudant-Chef Rekeraho, he was directly involved in the assassination of Queen Gicanda on April 20, 1994.

Queen Rosalie Gicanda was executed on the orders of Captain Ildephonse Nizeyimana at her home near the Ngoma Commune office. Gakwerere, then a lieutenant, was among the soldiers dispatched to carry out the killing. Others in the execution squad included Lieutenant Bizimana, known as Rwatsi, Corporal Aloys Mazimpaka, and Dr. Kageruka. The Queen was taken away and shot, along with several others who were with her, including Jean Damascène Paris, Alphonse Sayidiya, Marie Gasibirege, Aurelie Mukaremera, and Callixte Kayigamba.

For his role in the genocide, Nizeyimana was later convicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and sentenced to 35 years in prison, while Lt. Col. Muvunyi received a 15-year sentence. But Gakwerere evaded capture, fleeing to the forests of eastern DRC, where he became a senior leader of the FDLR, an armed group largely composed of genocide fugitives.

For years, he operated in the shadows, orchestrating attacks and terrorizing civilians from his base in the DRC. He believed himself untouchable, a warlord with power and influence. Yet, justice has a way of catching up. Today, clad in the uniform of the Congolese army, he stands defeated.

The images of his capture tell a story of poetic justice. The once-boastful figure, draped in green fatigues, an arrogant presence in the forests where he plotted his destruction, now finds himself subdued and in the grip of fate. Behind him, a procession of defeated men—some in military gear, others in civilian clothes—march under the watchful eyes of security forces. Among them are the remnants of a collapsing dream: fighters who once followed him into war, now disarmed and powerless.

But the most haunting image is that of the children—innocent, lost, and trapped in a war they never chose. Gakwerere did more than wage war; he stole futures. He ripped sons from mothers, turned boys into cannon fodder, and shattered homes. The pain he wrought is etched in their hollow eyes, in the confusion written on their young faces. These are the silent witnesses to his cruelty, the living evidence of his crimes.

His capture is not just a military victory—it is a reckoning. For Rwandans, it is a moment of vindication, a reminder that no crime goes unanswered. The Queen—Rwanda—stands unshaken, her resilience unmatched, her enemies falling one by one.

Gakwerere’s uniform, once worn with arrogance, now serves as a badge of his downfall. Justice, long pursued, has finally come knocking.

Hopefully he will have the generosity for telling what happened that Rwandans decide to exterminate their brothers & sisters. Where did the hate of the nation come from?

How could they separate Rwanda from Rwandans?

Hopefully he will have the generosity for telling what happened that Rwandans decide to exterminate their brothers & sisters. Where did the hate of the nation come from?

How could they separate Rwanda from Rwandans?