President Félix Tshisekedi’s administration faces mounting criticism amid a worsening humanitarian crisis in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and allegations of authoritarianism and corruption.

Opposition leaders, civil society groups, and international observers say recent suspensions of provincial no-confidence motions are less about wartime necessity and more about consolidating power in a government struggling to manage conflict, corruption, and displacement of over seven million people.

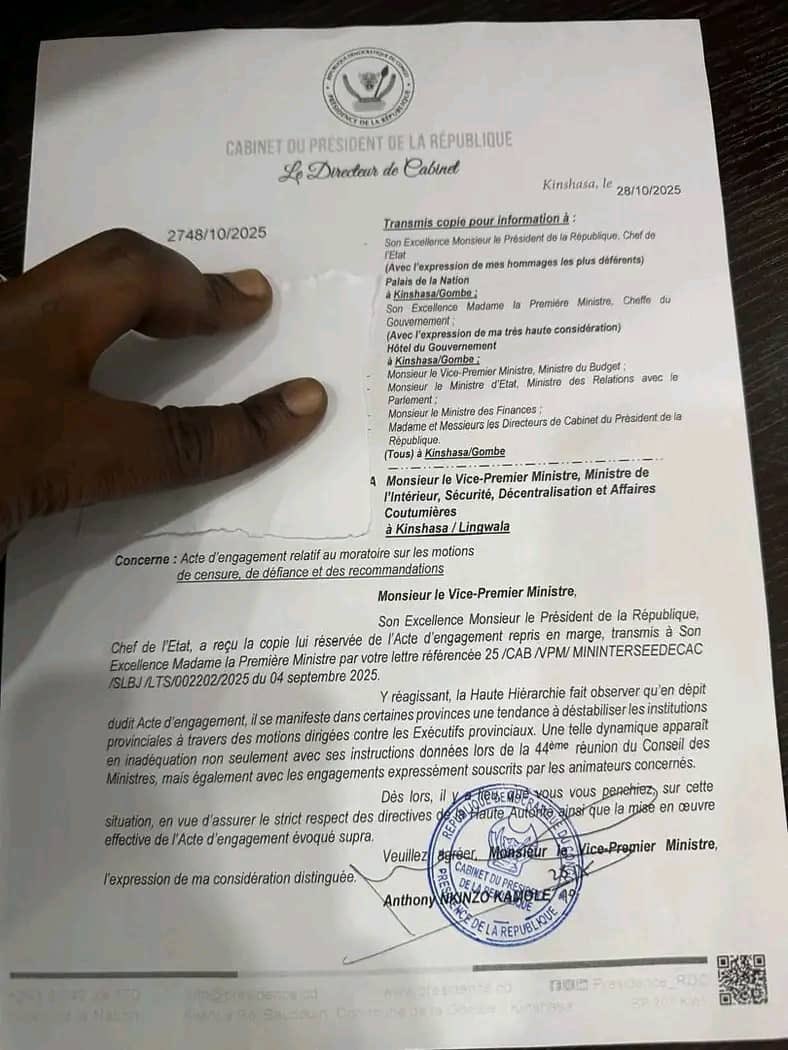

The controversy follows an October 28 directive from Tshisekedi’s Chief of Cabinet, Anthony Nkinzo-Kamole, ordering an indefinite moratorium on motions of censure in provincial assemblies, justified as a measure to maintain “institutional stability” amid the war with the M23 rebel group in North and South Kivu.

Critics fear the policy serves to protect allies and shield the administration from scrutiny.

They say this isn’t about security—it’s about survival.

The eastern conflict, which intensified in January 2025 with M23’s capture of Goma, has exposed weaknesses in the Congolese army.

Despite reinforcements from the Southern African Development Community (SADC), FARDC forces have suffered repeated defeats, attributed to corruption, poor pay, and failed reforms.

Soldiers’ accounts describe officers siphoning fuel and ammunition for personal gain, leaving troops under-equipped.

Tshisekedi’s promised military overhaul has yet to materialize, raising concerns that the conflict benefits elites financially.

Corruption scandals have compounded criticism.

In 2024, Tshisekedi’s chief of staff was convicted of embezzling $50 million, and allegations surfaced of officials paying millions to influence Washington, including claims that military inaction in the east was tied to graft.

Transparency International ranks the DRC 162nd out of 180 nations in its 2025 Corruption Perceptions Index. Public frustration has been amplified by musicians and social media campaigns calling attention to corruption and the ongoing war.

Tshisekedi’s administration has defended the moratorium, citing external threats and framing the measure as necessary to prevent destabilization by Kabila-linked factions.

Government supporters also point to achievements such as free maternity care and civil servant salary increases.

Yet stalled IMF-mandated reforms and opaque management of mineral revenues have weakened public confidence.

International observers, including Amnesty International and the European Parliament, have called for accountability, warning that the administration’s actions threaten democratic norms and human rights.

Legal challenges to the moratorium are underway, but the imprisonment of opposition figures complicates the path to reform.

For ordinary Congolese, the consequences are immediate. In Ituri, stalled anti-corruption probes and the ongoing war have left communities feeling paralyzed.

An assembly member told Kivu Today, “Tshisekedi fights for power; we fight for survival.” With thousands dead since January and reconstruction funds diverted or mismanaged, the president’s moratorium may buy time, but at the cost of public trust.